In modern networks, you rarely stick to just one hardware vendor—and that’s where MSAs (Multi-Source Agreements) come in. They define how transceivers like SFP, SFP+, and QSFP28 are built and how they’re supposed to behave, so modules from different brands can still work together.

Understanding MSA standards and SFP compatibility helps explain why some optics plug in and just work, while others cause link issues or vendor warnings.

An MSA (Multi-Source Agreement) is a technical specification created by a group of manufacturers working together, rather than by a single vendor. In simple terms, several companies agree on a common blueprint for a particular type of product—defining how it should be built, how it should behave, and how it should interface with the rest of the network. This blueprint can cover details such as the module’s physical dimensions, connector and pin layout, electrical signaling levels, and even thermal and mechanical requirements.

In networking, MSAs serve as shared reference documents that different vendors can design to. Because the technical details are clearly defined and publicly available, one vendor can build an optical transceiver or cable knowing it will physically fit and electrically interoperate with another vendor’s switch or router that follows the same agreement. This is especially important in multi-vendor environments, where equipment from different brands needs to work together as part of a single, cohesive system.

Ultimately, MSAs exist to make cross-vendor products work reliably together. By standardizing key design and behavior aspects, they help reduce interoperability problems, lower the amount of custom testing and integration work required, and give network operators more flexibility to choose hardware based on features and cost—rather than being forced to stay within one vendor’s ecosystem.

In networking, an MSA (Multi-Source Agreement) defines the technical details that let optical modules and related hardware work together across different vendors. These agreements describe a wide range of parameters, including:

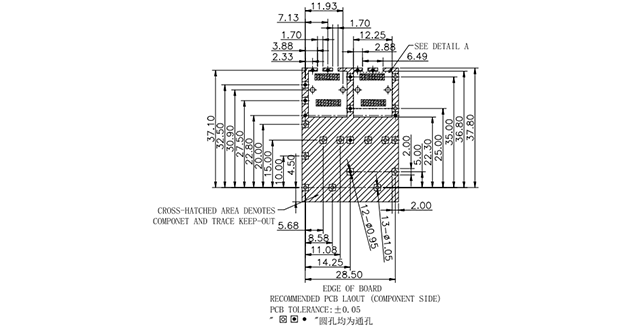

Physical form factor – overall shape, dimensions, cage design, and latch mechanisms

Electrical interfaces – signaling levels, pin assignments, and host-module interface behavior

Optical characteristics – wavelength, transmit power, receiver sensitivity, and link budgets

Thermal and mechanical parameters – heat dissipation, materials, and mechanical tolerances

By defining these characteristics in a shared specification, an MSA allows a module built by Vendor A to plug into a port from Vendor B and still negotiate power, signaling, and optical parameters in a predictable way—without guesswork, manual tweaking, or vendor-specific tricks.

In day-to-day operations, this means network engineers can mix switches, routers, and transceivers from different brands, bring links up smoothly, monitor them with standard tools, and swap modules when needed without redesigning the network. That kind of predictable interoperability is a core pillar of modern multi-vendor networks, where flexibility and easy interchangeability are just as important as raw bandwidth.

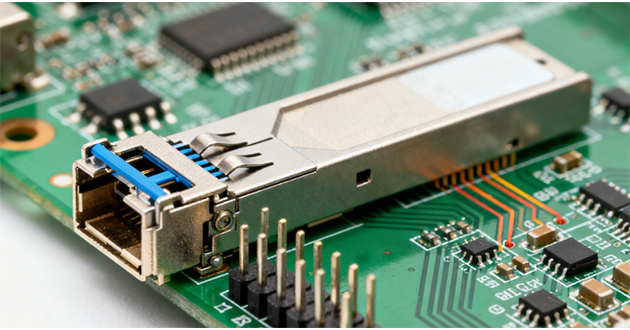

The SFP MSA (and its extensions such as the SFP+ MSA) does far more than simply name the Small Form-factor Pluggable family—it provides the technical blueprint that defines it. It specifies how an SFP is constructed mechanically, how it connects electrically to the host device, and how it should behave in terms of signaling, monitoring, and management.

These specifications cover details such as module dimensions, pin assignments, power limits, and optical performance, so that an SFP designed to the MSA can plug into any MSA-compliant port and operate as expected. In practice, the SFP MSA is what turns “SFP” from a loose marketing label into a true interoperable standard that vendors on both the module and switch side can confidently design around.

These agreements describe a wide range of parameters, including:

|

Category |

What It Covers |

|

Mechanical Specs |

Module size, cage, connector, cooling |

|

Electrical Interface |

Host-module signaling, pins, power/voltage |

|

Signaling & Optical |

Data rates, wavelengths, TX/RX levels |

|

Host Compliance |

Fit in MSA ports, proper init & operation |

An MSA-compliant SFP transceiver is built to an open, jointly agreed standard instead of a proprietary one. That shared foundation has very practical benefits for anyone designing, operating, or troubleshooting networks that rely on SFP optics.

Because MSA-compliant SFP modules follow the same mechanical, electrical, and optical rules, SFP optics from different vendors can be used in the same MSA-compliant port and still bring the link up as expected. How the SFP seats in the cage, powers on, and negotiates the link is defined in the specification, so you spend less time chasing “mystery” compatibility problems and more time focusing on actual network operations.

MSA standards give you room to choose, instead of forcing you into a one-vendor strategy for every SFP. You can select SFP modules based on price, availability, support commitments, or specific features such as lower power consumption or extended temperature ranges. That makes it easier to control costs and to grow or refresh the network without being tied to a single supplier for all your SFP optics.

Even though different manufacturers may use their own components and designs, MSA requirements keep all compliant SFP transceivers within defined electrical and optical limits. Link budgets, transmit power, and receive sensitivity stay within a known envelope, so mixed-vendor SFP links behave in line with your planning assumptions. That consistency makes capacity planning, performance tuning, and fault isolation more straightforward.

Day to day, MSA-compliant SFPs simplify work at the rack. If an SFP module fails, a technician can replace it with an equivalent SFP from another vendor without redesigning the link, retesting the optics, or changing the cabling. The same applies during gradual upgrades—you can introduce newer or more efficient SFP modules while leaving the rest of the path untouched. This reduces the number of spares you need to stock, shortens repair times, and lowers the risk of unplanned downtime.

For an SFP module to work reliably with a host device, simply fitting into the cage isn’t enough. It must meet the technical requirements outlined in the SFP MSA, which define how the module should behave mechanically, electrically, optically, and at the management interface level. These shared rules are what make multi-vendor SFP ecosystems possible.

MSA-compliant SFPs are built to identical physical dimensions and mechanical layouts—including the latch design, connector position, and overall footprint. This guarantees that any compliant module seats properly in an MSA-certified cage and aligns cleanly with the host connector. Uniform mechanics also help maintain consistent airflow and thermal behavior in tightly packed switches and servers, where even small variations could disrupt cooling or module stability.

Electrically, the SFP MSA defines how the module interfaces with the host—covering pin functions, allowable voltage ranges, startup behavior, and maximum power draw. These limits ensure that inserting an SFP won’t overstress the line card’s power rails or introduce unpredictable signaling. Because every compliant module follows the same electrical expectations, it can communicate with the host PHY at high speed without needing vendor-specific adjustments or board-level workarounds.

The MSA also standardizes how the SFP and host exchange identification and management information. The EEPROM map and I²C communication structure define where details like module type, supported speeds, wavelength, digital diagnostics, and threshold values are stored. Since every compliant SFP uses the same layout, switches and NICs can read and interpret module data consistently, apply the correct settings, and expose reliable telemetry—regardless of who manufactured the optic.

Optically, the SFP MSA specifies the performance ranges for different module classes: wavelength, transmit power, receiver sensitivity, and eye-mask characteristics. These parameters are what ensure that two ends of a fiber link speak the same “optical language.” When both SFPs adhere to the same class of MSA requirements (e.g., SR or LR), light levels and signal shape fall within expected bounds, making the link budget predictable and reducing the chance of marginal or unstable connections.

If both the SFP module and the host port follow the same MSA, each layer—from mechanical fit to optical signaling—lines up cleanly. The result is a stable, interoperable SFP link that behaves the same regardless of which vendor’s logo is on the label.

Examples of MSA-Based Transceiver Standards

|

Transceiver Type |

Nominal Speed |

Brief Description |

|

SFP |

1G |

Original Small Form-factor Pluggable standard for Gigabit networks. |

|

10G |

Enhanced SFP that supports 10G while retaining the same compact form factor. |

|

|

25G |

Higher-speed evolution of SFP+, using improved electrical/optical design for 25G. |

|

|

40G |

Quad-lane transceiver delivering 40G as 4 × 10G channels. |

|

|

QSFP28 |

100G |

100G module using 4 × 25G lanes, defined through QSFP28 MSA. |

These form factors all rely on MSAs so that different manufacturers can build transceivers and ports that interoperate seamlessly.

Read more:

Conclusion

MSAs form the backbone of optical transceiver interoperability, ensuring that modules from different manufacturers fit, power up, and communicate in a predictable way. By defining everything from mechanical dimensions to electrical behavior and optical performance, these agreements allow SFP-based networks to operate smoothly across mixed environments and evolving generations of hardware.