This article explains the difference between an RJ45 port and an Ethernet port, clears up common myths, and shows when to choose an rj45 connector, optics, or DAC in real networks.

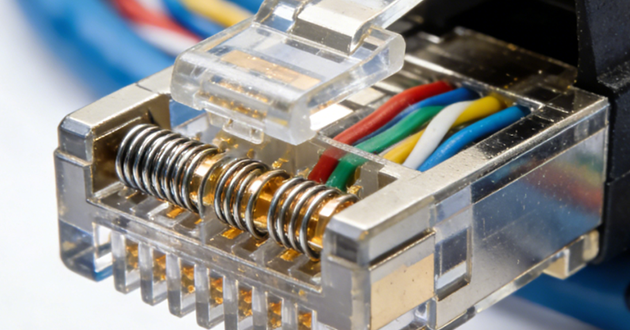

An RJ45 port is the familiar latch-style rectangular socket you click an rj45 connector into—the copper workhorse on routers, switches, PCs, NAS boxes, and wall plates. Electrically it’s an 8P8C interface: eight spring contacts in the jack touch eight gold-plated pins in your plug, mapping to four twisted pairs in Cat5e, Cat6, or Cat6a cable. With 10/100 Mbps, two pairs carry data; Gigabit and faster use all eight conductors. Most modern RJ45 ports also speak PoE, so one cable can deliver data and power to low-voltage gear like IP cameras or ceiling APs—handy where AC outlets are scarce.

Beyond the basics, a few details matter for real-world reliability. Quality jacks are rated for hundreds to over a thousand insertions, and integrated magnetics behind the port help reject noise and protect the PHY. Auto-MDI/MDIX means you don’t worry about crossover wiring anymore; the devices sort that out. In structured cabling, you (or your installer) typically punch solid cable onto a keystone jack and then use a short factory patch lead—this preserves the channel spec and spares your device’s port from constant wear. If you crimp your own rj45 connector, keep pair twists right up to the contacts, trim cleanly (pass-through plugs help on Cat6/Cat6a), and mind strain relief so the termination doesn’t creep over time.

An Ethernet port is any physical interface that sends and receives Ethernet frames—it’s a function, not a shape. On twisted pair you get BASE-T ports that look like RJ45 and span 10/100/1G/2.5G/5G/10G, with 100-meter channels when the cable category matches the speed (e.g., Cat5e for 1G, Cat6 for 10G to ~55 m, Cat6a for 10G to 100 m). In servers and higher-end switches, an Ethernet port might instead be a pluggable cage—SFP/SFP+ (1G/10G), SFP28 (25G), QSFP+ (40G), QSFP28 (100G) and beyond—accepting fiber modules or direct-attach cables. Those options trade the simplicity of an rj45 connector for reach, density, and power advantages: 10GBASE-SR often covers ~300 m on OM3 multimode fiber, while LR single-mode stretches ~10 km; DAC is the go-to for short, low-latency rack runs.

In practice, RJ45 connector is the everyday face of Ethernet at the access layer, while pluggable optics and DAC dominate aggregation and backbone links. Same protocol family, different physical presentation.

At home and in most small offices, “Ethernet port” almost always means the RJ45 jack. Copper runs are inexpensive, pre-made patch cords are everywhere, and installing a keystone or crimping an rj45 connector is straightforward—so you plug a PC, printer, or TV into the “Ethernet port” and forget about it.

Step into a wiring closet or server room and the term broadens. The uplink labeled “Ethernet” on a core or aggregation switch could be an SFP+ cage awaiting a 10G optic, or a QSFP28 slot for 100G. Visually, an RJ45 is a small rectangle with a plastic latch and visible contacts; SFP-family cages are longer, metallic, and built for hot-swappable modules with bail latches. Status LEDs often sit beside RJ45 jacks; pluggable cages show link/activity on the module or nearby panel. In short: for consumer gear, Ethernet port ≈ RJ45; for rack hardware, it might just as well mean “bring the right optic.”

The big one: “RJ45 = Ethernet.” Not quite. RJ45 names the 8P8C rj45 connector form factor; Ethernet is the networking family that can ride over that connector—or over fiber and DAC. They overlap constantly but aren’t synonyms.

Phone plugs vs. data ports is another trap. RJ11 (6P2C/6P4C) is smaller and pinned differently; forcing it into an RJ45 jack can bend the outer contacts and set you up for intermittent links later. If you inherit old cabling, confirm jack types before reuse.

Finally, swapping to a “better” rj45 connector doesn’t magically unlock 10G. Throughput is capped by the weakest part of the channel: cable category and length (10GBASE-T typically wants Cat6 to ~55 m or Cat6a to 100 m), termination quality (twist maintained to the pins, correct strip length, proper strain relief), EMI conditions (shielding/grounding where appropriate), and whether both endpoints actually support 10GBASE-T. Also note 10GBASE-T runs warmer and draws more power than 1G, so 2.5G/5G (NBASE-T) is often a pragmatic mid-step on existing copper.

Home & SOHO. RJ45 jack is the default for desktops, game consoles, and TVs. Moving latency-sensitive devices from Wi-Fi to copper cuts jitter and buffering; on a quiet LAN, you’ll often see single-digit-millisecond latency versus the variable tens common on congested wireless. A small unmanaged switch plus a few Cat6 patch cords is a low-effort stability upgrade, and terminating a wall plate with an rj45 connector is manageable with a punch-down tool and a basic tester.

SMB offices. RJ45 plus PoE keeps rollouts clean. A 24-port PoE switch with ~370 W budget can power a realistic mix of endpoints—say, 6–10 W cameras and 13–25 W Wi-Fi 6/6E APs—over the same Cat6 that carries data. You eliminate wall warts, centralize backup power via the switch’s UPS, and expand by simply patching new drops into structured cabling.

Data-center & uplinks. For top-of-rack to aggregation, pluggable optics or DAC usually win on density, power, and reach. Use DAC for 1–3 m server-to-switch links, 10/25G SR optics for ~100–300 m in-row runs, and LR for building-scale distances. 10GBASE-T over RJ45 is useful for mixed environments or staged upgrades, but mind Cat6/Cat6a limits and higher power draw compared with optics.

Industrial & harsh environments. Plan for EMI, dust, moisture, and vibration. Choose shielded twisted pair with proper bonding, rugged metal-shell jacks, strain-relief boots, and—where needed—sealed housings such as IP67 RJ45. Many PLCs, machine-vision cameras, and panel PCs still rely on copper Ethernet; selecting the right rj45 connector (shielded vs. unshielded, office vs. industrial) and enclosure rating is what turns a lab demo into a system that runs for years on the plant floor.

Conclusion

An RJ45 port is a defined copper connector, while an Ethernet port is a broader category that can include RJ45, SFP, QSFP, and more.